It has been established that the Japanese Canadians were hardworking, generous, and loyal to Canada. It has also been established that their broad reputation in BC and Canada was negative, but in smaller communities they were seen in a positive light. Why this dichotomy? Was the broader Canadian citizen just racist against Japanese individuals? I mean, come on, probably, but there is a lot of evidence which proves the tension to be deeper, and more quantifiable. Examining the relationship through previously discussed frameworks, we see that many white workers saw Japanese workers as an economic threat. With the assumption that their gain means our loss, it becomes easy (although not justifiable) to understand why the broader white Canadian had a negative view of Japanese Canadians. Most Japanese Canadians lived in smaller communities, kept to themselves, and were known to be harder workers than white Canadians. All these factors would lead to someone not having any experience or contact with Japanese individuals, and therefore either not having an opinion one way or the other or leaning towards dislike. Add in the broader narrative and anger that a very vocal minority held towards the Japanese, and that uncaring majority start to err on the side of the hateful narrative. In contrast, those who worked and lived more closely to Japanese families saw them as friends and co-workers. Relations in Mission were starting to better, and there was much less animosity held towards these individuals.

Looking at the relationship between Japanese individuals and White individuals during the Great Depression is interesting as well as difficult. We see through documentation that most Japanese families started to immigrate to Canada in the late 1910’s and throughout the 1920’s. This would infer that the Japanese-White relationship would not be particularly well developed before Canada’s economy started its decline. Moving forward into the 1930’s this relationship, which hadn’t been fully formed, would see itself under heavy stress. Many white Canadian families saw themselves in a pickle during the Depression. Unemployment was rising, loans were being defaulted on, and people were scared for their future. This is when we see resentment towards foreign workers start to build. Some white Canadians were upset that people who they saw as non-Canadians were still employed and profiting when their friends and families and themselves were unemployed and scrounging for anything they could. Groups like the “White Canadians Association” asked for “any alien who is not capable of being assimilated by absorption or whom we do not wish to absorb” to be prohibited from entering Canada. The White Canadians Association of course having members of the Retailer’s Association, the Fisherman’s Protective Association, the Cloverdale Farmers Association as well as real estate agents on their executive committee, all areas where the white Canadians would have felt pressure from Japanese Canadians. This resentment didn’t come out of thin air, and the conditions of the Depression thus worsened relations.

Small Town Relationships

In smaller communities such as Mission, relations between Japanese and white individuals were better. No one wrote down exactly why they felt the way they did but looking at the societal differences in smaller communities as opposed to larger ones and comparing that to the causes of the animosity we have previously established, it is possible to paint a fuller picture of why relations in smaller communities were better than in larger ones. Using the previously established framework of education, labour, and community, lets run through the Japanese-White dynamics during the depression using Mission as an example.

On the education front we have a couple of examples in Mission to examine. The education board in Mission set up a kindergarten primarily for Japanese children. Their aim was to have these students have an understanding of English and broader Canadian culture and customs before entering the main body of public school. The Japanese families obliged, and the students had success throughout their education. What is worth noting however, is that it was not only Japanese children who attended this school. There were also white children over the years who attended, which also helped progress their education as well. We see here that families were not so against Japanese individuals to as to have their students miss developmental years. The Japanese families having their kids attend kindergarten to better develop their inner “Canadian” lines up directly with the Japanese Education Societies aims and goals and seemed to foster better relationships between Japanese and white families in Mission.

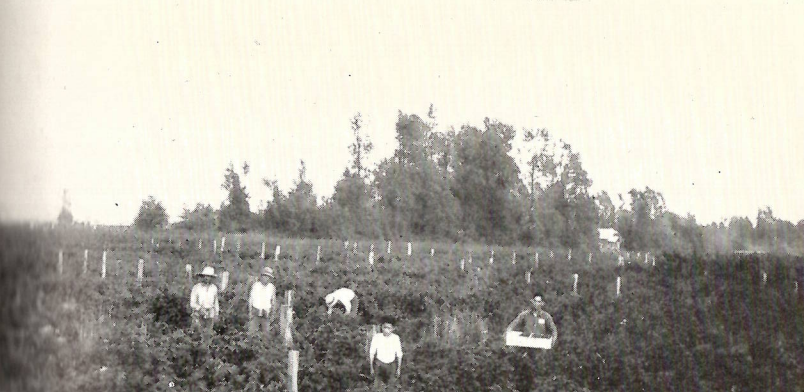

The labour interactions have been touched upon previously in great detail but is worth going over again with a Mission-specific lens. It is here where we see the birth of the Pacific Cooperative Union, a berry growers union which saw Japanese and white farmers working together, not only in the fields but also on their board of representatives. The PCU worked to standardize the way berries are packed and processed and negotiated shipping rates across Canada. The PCU worked to build a jam processing facility which helped farmers greatly, as well as pressuring legislature for things like limiting the amount of filler allowed in jams, which further benefitted farmers, both Japanese and white. To go a step further on the labour front, even the White Canadians Association, the most vocal antagonists of the Japanese Canadians, agree that they were excellent workers.

With labour wrapped up that just leaves community interactions to examine in Mission. Throughout the 1930’s we see quite a lot of mentions of Japanese contributions to events in the newspaper. From monetary donations, helping with construction, and shows, to dances, firework exhibits, and so much more, we see the Japanese families in Mission interact with the broader white community a lot more than in larger communities. These more common and community building interactions lead directly to stronger relations between Japanese and white Canadians in Mission and helped with the breaking down of walls between racial groups.

These three areas together show us an image of what small-town-depression-era-Canada was like. Groups of people working together to bring everyone up. While there were bits of racial division here and there, the preeminent theme is one of shared struggle and even comradery and relative unity. Small towns saw the start of the dissolution of the “Us vs Them” mentality and learned to work together to get each other through tough economic times.