Throughout BC, we see the Japanese immigrants being treated differently than white workers. In the fishing and forestry sectors, sectors where Japanese workers first started when they came to Canada, sources point towards a large amount of resentment towards the Japanese. So much so that laws were put in place limiting the number of Japanese individuals who were allowed to work in those industries, and this led to many Japanese families becoming farmers, as it was one of the few areas where the number of laborers were not capped. To get a better understanding of the Japanese Canadian position in Canada and British Columbia, one can examine the education sector, the labour sector, and the civic sector.

Education

Looking at translated writings from the Canada Japanese Language School Education Society (CJLSES), we see that their main goal of education, first and foremost, was to make their students better Canadian citizens. They sought to educate the Nisei (Japanese children born in Canada) in the Canadian manner first and give them an education in Japanese language and culture second. They recognized that the future would be hard for Canadian-born Japanese, and that having them well versed in both Canadian language and culture and Japanese language and culture would provide the students with the largest benefit. On top of the perceived benefits, the CJLSES wrote on how students educated in both Canadian and Japanese matters would be very well suited for dealing with conflicts between Canada and Japan. They write “Conflicts between nations occur mostly from mutual misunderstanding. Having an understanding of both languages and cultures would help prevent conflict and promote friendship.” It should be stressed; this was the Japanese viewpoint on education in the early 20th century. Many white Canadians saw the Japanese Language schools not as a way for Japanese students to learn and develop strengths to help resolve issues between nations, but as a way for Japanese students to reject Canadian learnings and double down on their Japanese ancestry – the exact opposite of the goals of the CJLSES.

Labour Relations

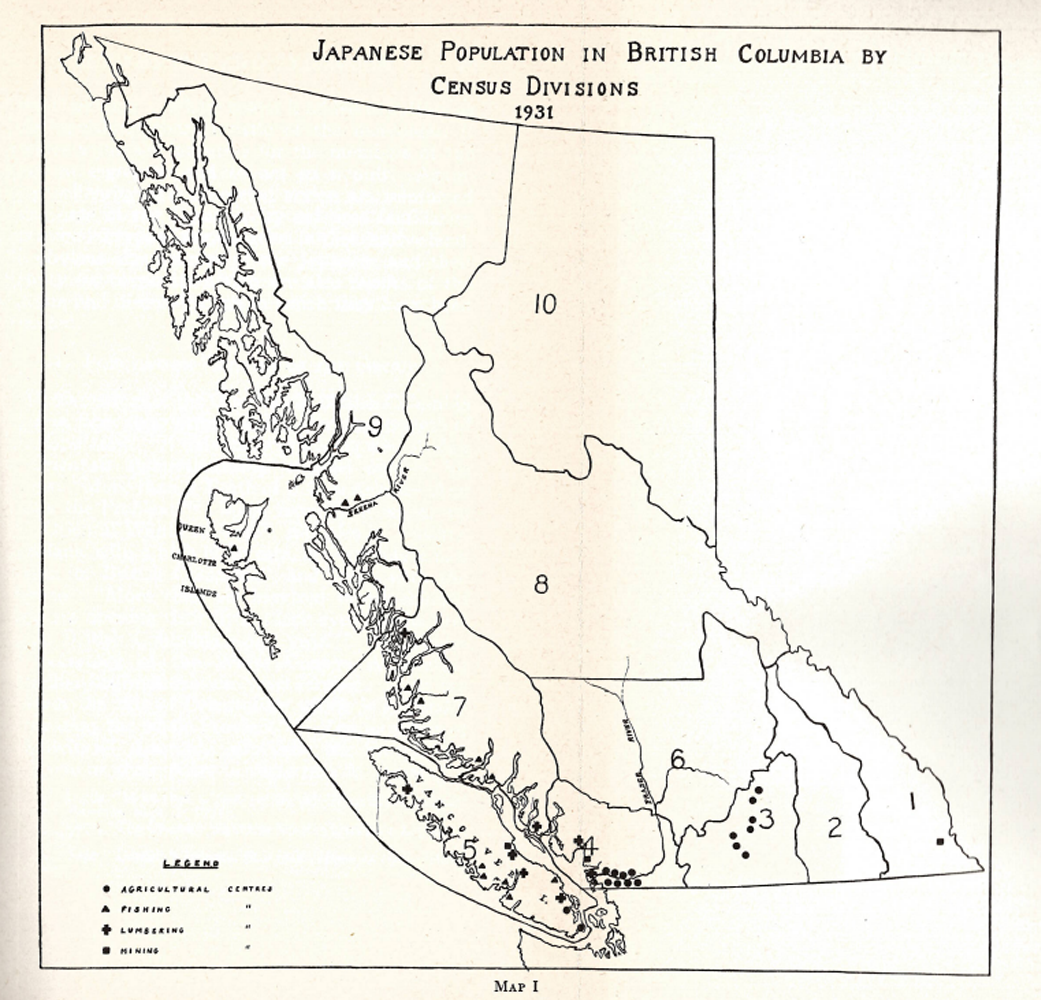

On the topic of worker relations between the Japanese and White Canadians, there are only a few places we need to look. As Japanese immigrants began to settle in BC they primarily went to a few industries, mainly fishing, logging, and some in general labour. With that said, once too many began working in the fishing and logging industries the Canadian government began to limit or ban Japanese workers from employment in those industries. Fishing licences were limited in quantity for Japanese fishermen, which led directly to a reduction in Japanese fisherman. The provincial government also implemented measures to reduce the number of Japanese immigrants in the lumber industry, which worked exactly as planned. With these two major industries strictly limiting the employment of Japanese Canadians however, only two options remained for them; return to Japan or find a new industry. While a small percentage chose the former, a great many others chose the latter, leading to a boom in the number of Japanese farmers in British Columbia. Some data from the 1930’s shows us that Japanese farmers held about 28% of the farmland in BC but produced about 85% of all berries grown.

It should be noted that the exsanguination of the Japanese from fishing and lumbering was not done merely on the government’s whim. The white workers in these industries saw them as competitors and applied immense pressure to the government to protect them and their livelihoods in these industries. Many texts discuss the work ethic of the two groups, often stating that the Japanese Canadians were harder, more productive workers. Again, it was the white workers that were complaining about the Japanese workers, not the employers. This is worth mentioning as both the white workers and Japanese workers were under a common struggle, but many of the white workers saw the solution to the problem to be the removal of Japanese workers from their industry, not better pay, benefits, and social safety nets for all. In other words, the tension they were feeling was directed at their peers, more than the conditions themselves. This is worth keeping in mind while looking at the future of the Japanese in British Columbia.

I digress. As the Japanese left the lumber and fishing industries, we see a steep rise in farming in the Fraser Valley. Japanese workers headed out to the Valley, purchased land that many other settlers assumed to be marginal for farming due to trees and the like, and forged highly productive and efficient farms on said land. As mentioned previously, the Japanese farmers were responsible for a vast majority of the berries produced, and in later years also hops. In the Fraser Valley some of the Japanese farmers got together with some of the white farmers and, after some administrative back and forth, formed the Pacific Cooperative Union. This Union covers a lot of the Japanese work force throughout the 1930’s. Forming in 1932 with 70+ Japanese and 30 white farmers, the PCU started off immediately as a successful business venture. In 1934 the PCU had over 200 members, 2/3 of whom were Japanese, and it only grew from there. More members. More berries. More money. The 1930’s were a very successful time for the Japanese farmers, as well as white farmers, even with all the stress and economic turmoil of the Depression years. After being pushed out of two other industries, it seems like the Japanese Canadians had finally found a home. It’s a good thing this all got resolved in the end, it would be awful if something terrible happened to these preserving workers.

Societal Collaborations

Societal interactions must also be analyzed and contextualized. There isn’t a ton to discuss, but it is important. Throughout the 1930’s, from texts and newspaper sections, we see Japanese Canadians contributing to community events, participating in Canadian holidays and parades, donating to hospital funds, assisting in the construction of community buildings and – moving into wartime – purchasing their fair share of war bonds. This may all sound completely reasonable to you dear reader, but one must recall that the Japanese workers were painted as being wholly nationalistic to Japan. So, while we cannot completely dismiss the claim that some of them might have been, the integration of Japanese workers into the Canadian social-scape should not be overlooked. This would most likely be why in smaller communities, such as Mission, the Japanese-White relationship was much better than on the broader scale of BC. It should be noted that while relations were better in smaller towns such as Mission, this was still early in the breaking down of racial divisions in labour and society. Taking these actions, as well as the Educational Societies goals of creating loyal, hardworking Canadian citizens, one can only reasonably conclude that a majority of Japanese Canadians saw themselves as Canadians and wanted to do their best to fit in and foster better relationships between nations. They recognized themselves as a outside group and wanted to assuage the fears of white Canadians who thought the influx of Japanese immigrants meant the end Canada as they know it.